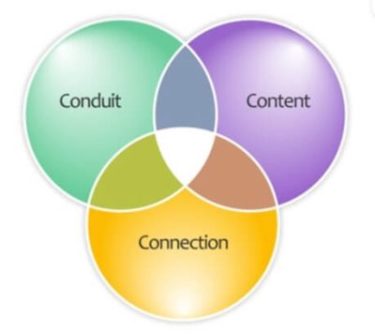

The central model of our training methodology (adapted from Aristotle’s work a few millennia ago), says that great communication lives at the intersection of what you say, how you say it, and the relationship that exists between the speaker and the listener. On an intellectual basis, we get essentially no pushback on the validity of this model.

An oft-repeated adage, “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it,” was probably created by parents tired of teenagers’ eye rolls and sarcastic tone. But it’s not true. What you say most definitely matters. It’s why we use the model that says the intersection of the elements is where true greatness lies.

But very few clients want training on content development. After all, they are the experts in what they want to say. They have the facts, details, and experience that gives them the right to speak in the first place. I’ve coached clients who were experts in cancer research, the design and manufacture of life-saving drugs, helping expand agriculture business in rural Africa, solving the problem of cybersecurity, running election campaigns, and managing large-scale commercial real estate projects. My knowledge base has almost nothing to offer any of them on the details of their content. But crafting a good message and the nuances of how you share what you know is critical. And I don’t need to know your topic to help you in delivering a powerful message around it.

One set of mistakes I frequently see are people whose expertise leads to dogmatic statements and advice. There’s a time and place to lay down the law and state truth and facts with conviction and perhaps even a hint of superiority. But when trying to convince or persuade or sell or win people over, this approach can backfire. Here are three phrases I usually coach people to avoid, and an approach that invites dialog and conversation instead of dismissal:

- You need to… The fact may be that the person does need to. You may have superior knowledge and wisdom that makes this a tempting statement to make. But in general, people don’t respond to being told what they need to do. “You need to lose weight…” has rarely made a diet successful.

- You have to… There aren’t many things that rise to the importance of “have to”. You don’t have to get out of bed, go to work, or even eat. The consequences of not doing so can be disastrous, but you don’t have to. I frequently correct people when they say “I have to…” by reminding them “You get to…” It’s a minor mindset change. But you always have a choice. To quote a rather rebellious friend of mine from high school, “When someone tells me I have to do something, I’m pretty sure I don’t.”

- You ought to / should… This has implications that you know what is right/wrong about someone else’s situation. And you may. At least in your mind and in your world view. But even when someone knows they ought to do something, it often isn’t enough to motivate them to action. That’s why we have dentists and fitness studios and nutritionists. We need something more than the knowledge of what we ought to do.

These are easy phrases to make. But they aren’t likely to create the outcome you want. Instead, limit the discussion around your observations and experience. Instead of telling your child that they need to set their alarm ten minutes sooner to get ready on time in the morning, you might say, “I’ve noticed that when your alarm goes off ten minutes before departure, you aren’t ready in time.” Instead of telling your staff they ought to implement a new data point in their sales presentation, you might observe that you’ve used the phrase three times in the last week that resulted in $50k in new business.

One word of caution: limit your statements to observable fact. Don’t dive into the assumptions of the motive behind the behaviors you see. Phrases like “You assume…” or “you think…” are presumptive at best. You can’t observe assumptions and thinking. “I heard you say…” or “I’ve seen…” are good starts.

The great thing about using observation over categorical advice is that it (usually) cannot be argued with. If I notice that you are late when your alarm isn’t early, then you can justify it, but you can’t deny it.

What you say and how you say it both matter. But even within the very-important context of what you say, there are better ways to communicate your message. Refine and practice methods that draw your audience to the conclusions you want, instead of passing out those conclusions with no opportunity for your listener to think about and adopt your point of view.

Communication Matters. What are you saying?

Want more speaking tips? Check out our Free Resources page and our YouTube channel.

We can also help you with your communication and speaking skills with our Workshops or Personal Coaching.

This article was published in the August edition of our monthly speaking tips email newsletter, Communication Matters. Have speaking tips like these delivered straight to your inbox every month. Sign up today to receive our newsletter and receive our FREE eBook, “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation.” You can unsubscribe at any time.